The fight over Prince’s estate will dig deep into copyright law for a very long time

When Prince passed away on April 21, 2016, he left no will, and now his heirs appear ready for a long fight over his estate. Apparently, their first meeting about the estate ended in shouting. Heirs can battle over any substantial estate, and there are particular complications when it involves an artist. Some of what Prince’s heirs are fighting over is the ownership of his works — his published and unpublished music compositions and recordings. Copyright law will have a significant impact on who has what rights, and for how long. Three particular areas affecting their rights are the termination of transfer (17 U.S.C. § 203), the term of copyright for published and unpublished works (17 U.S.C. § 302), and the contracts already in place. The drafting of a will for an artist, or the administration of a late artist’s estate, should include a consult from an attorney for copyright due diligence.

After 35 Years, Artists and their Estates Get Another Bite at the Apple

There is an inherent feeling of unfairness for an artist when they sign away the rights to their works, which against all odds go on to become popular and make a fortune for the rightsholder — and not the artist. To address this, the Copyright Act built in a “termination of transfer” provision that gives an author an opportunity to claw back their works after 35 years, essentially giving the artist “another bite at the apple.” 17 U.S.C. § 203. There are court cases about termination of transfer for “Santa Claus is Coming to Town,” Winnie the Pooh, Archie Comics, Ray Charles, the Village People and a few others, but there aren’t very many published opinions offering guidance about interpreting the law. The battles over the Prince estate may explore these issues for decades.

Most of Prince’s Works are Owned by the Estate and Licensed to Warner Bros.

Prince’s first album For You was released in 1978, but still earns money for its publisher Warner Bros. Records to this day. Had Prince wanted to, in 2013 he could have rescinded the rights to distribute his 1978 album from Warner Bros. In 2014, he could have terminated the transfer of his 1978 or 1979 albums, and reclaimed control over them. Had he wanted, he could have kept terminating transfers as his most popular albums hit their 35 year mark: Controversy (2016), 1999 (2017), Purple Rain (2019), Around the World in a Day (2020), Parade (2021), Sign o’ the Times (2022), Lovesexy (2023), Batman (2024), Graffiti Bridge (2025), Diamonds and Pearls (2026) and so on. Instead, in 2014 Prince and Warner Bros. Records redid their deal, which apparently resulted in Prince’s reclaiming ownership in his back catalogue, and Warner Bros. retaining certain rights to distribute his music. This effectively resets the clock on the termination right, which can’t be exercised against Warner Bros. for the works covered by this agreement until 2049. Warner Bros. and other record labels appear to be quite flexible in redoing deals with their artists with still-popular back catalogues that are approaching their 35-year termination of transfer dates. Musicians are finding that the evolution of digital recording and distribution give them much more of an ability to exploit their works without the help of a record label, which gives them even more leverage to get even more favorable deals if they renegotiate. The termination of transfer right and technological advances are giving artists just the second bite at the apple envisioned by the termination of transfer clause’s authors — as long as the artists and their heirs have the legal counsel to help them take advantage of it. Warner Bros. chose to do what it could to lock up Prince’s most lucrative works in the face of a termination of transfer.

Prince’s Estate can Already Claw Back Some of his Other Works, and More Every Year

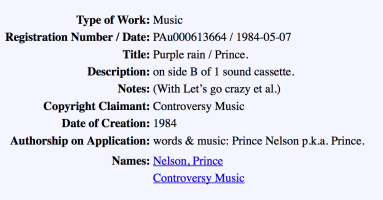

However, there may be other licenses and transfers of rights in Prince’s works that were not affected by the Warner Bros. agreement. The oldest of these licenses and transfers are eligible for termination, and more will be in the coming years. The mechanics of the termination are a bit complicated, but are based on the passage of 35 years since the initial transfer of copyright. For the purposes of illustration, imagine that shortly after Prince released “Purple Rain” in 1984, he licensed the song to Hallmark for exclusive use in musical greeting cards. Even if the contract said that Hallmark had the right to make “Purple Rain” greeting cards for the entire duration of copyright, Section 203 allows Prince to terminate that license after 35 years. The termination can take place as early as 2019, or within five years after that in 2024. It’s a five-year window to terminate — after that, Prince would have lost his chance. To terminate a transfer related to “Purple Rain” as early as possible in 2019, Prince would need to notify Hallmark between 2009 and 2017, since the law calls for written notice no more than 10 and no less than two years before the termination would take effect. During that time between the notice and the termination, the original parties can renegotiate their deal, in this case Prince and Hallmark. If they couldn’t come to an agreement, the termination takes effect, and the greeting card rights to “Purple Rain” would revert to Prince. Only after the termination took effect could Prince make a new deal with another party for “Purple Rain” greeting cards. There are many other contours to the law, and there is very little caselaw on how it works, so it is ripe for controversy and error without the guidance of an attorney who understands the process. And because Prince has passed, there is the further question of who (if anyone) can terminate a transfer in the first place.

Who can Pull the Trigger? Not Prince’s Siblings

There may end up being an interesting split between who owns the copyright to Prince’s work, and who has the right to terminate a transfer. Under Minnesota state law, Prince’s estate, including his copyrights, will descend to his sister Tyka Nelson and their five living half-siblings. (More than 700 people have claimed to be Prince’s half-sibling, but none have yet been recognized by the court.) But under the termination of transfer law, siblings of the author do not have the right to terminate. Section 203 says that widows/widowers, children and grandchildren are the family members who have termination rights. Prince left no living widow, children, or grandchildren, so none of that applies to his works. According to the termination law, siblings are not next in line — “In the event that the author’s widow or widower, children, and grandchildren are not living, the author’s executor, administrator, personal representative, or trustee shall own the author’s entire termination interest.” So who will “inherit” Prince’s right to terminate the transfers in his works? Who will actually get the second bite at the apple?

The Fight to be the Administrator

As of this writing, the termination of transfer right is owned by the court-appointed “special administrator” the Bremer Trust, which provided financial services to Prince for many years. “Administrator” is one of the entities recognized by the termination of transfer law. The Bremer Trust was appointed special administrator by request of Prince’s sister Tyka Nelson. The Bremer Trust could exercise Prince’s termination rights for older works now, and may even find it necessary to do so given the strict deadlines of the termination right. However, the special administrator should be replaced within six months by a more permanent representative. Tyka or any of the other siblings could seek to be named Prince’s administrator, and the court could also name the Bremer Trust or another neutral party. An administrator is typically thought of as being a functional role, carrying out the best interests of the estate, distributing property by function of law and not operating for its own benefit. However, the termination of transfer creates a strange situation where the administrator him or herself becomes the owner of the terminated right (or work, if it was transferred in its entirety). It is not clear whether the administrator is required to redistribute any terminated rights to Prince’s heirs, all of whom would be well-advised to raise these issues before the permanent administrator is appointed by the court. There may be a contractual agreement among the administrator and the heirs or a court order concerning the exercise of the termination of transfer right, but the actual termination must be made by the court-appointed administrator, the only party recognized by the Copyright Act. Unless addressed by the court, this means that the heirs who own Prince’s works by the mechanics of estate law could lose their rights to their own administrator slowly over time through termination of transfer. There will certainly be a struggle among the parties over the selection of a favorable administrator, who may not be bound by any restriction with regards to termination of transfer. There could be a contractual agreement between the heirs and the administrator, but the statute may make such an agreement unenforceable. The court’s order in establishing the administrator — and its interpretation of the statute — could be worth a fortune.

Most of Prince’s Works are Protected through 2086

The fight will likely go on for a long time. But it will come to an end on a date certain for most of Prince’s works. It is very unusual for works to be commercially valuable through their entire term of copyright. There are millions of works in the Copyright Office registry that have been all but forgotten. But Prince is the kind of iconic, transformational artist whose works could very well still be earning money for generations. Under current law, the term of copyright protection is the life of the author plus 70 years, which in Prince’s case is 2086. This applies to both Prince’s published and unpublished works.

Who is Alexander Nevermind?

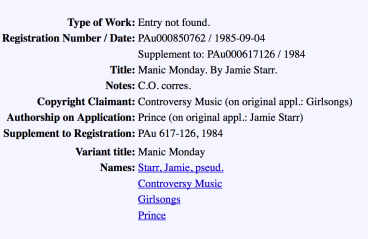

Prince also wrote under several pseudonyms, including Jamie Starr, Joey Coco, Alexander Nevermind and Christopher, and occasionally used those names for the copyright registration. Copyright for pseudonymous works lasts for 95 years from publication, or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first. 17 U.S.C. 302(c). Some of these were registered with the Copyright Office to Prince, even though they were publicly credited to one of his pseudonyms. However, if a simple supplement is filed with the Copyright Office, the term of copyright and the termination of transfer rights remain the same, as if Prince had been credited as the author in the first place. 17 U.S.C. 302(c), § 408(a), (d). This has already been done for many of these pseudonymous works, such as “Manic Monday.” The heirs could choose to leave the registration pseudonymous, but that would likely result in a shorter term of copyright. Prince used pseudonyms primarily in the early part of his career, and works published pseudonymously before 1991 and left unclaimed would expire earlier than the 2086 expiration of works credited to Prince.

Prince also wrote under several pseudonyms, including Jamie Starr, Joey Coco, Alexander Nevermind and Christopher, and occasionally used those names for the copyright registration. Copyright for pseudonymous works lasts for 95 years from publication, or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first. 17 U.S.C. 302(c). Some of these were registered with the Copyright Office to Prince, even though they were publicly credited to one of his pseudonyms. However, if a simple supplement is filed with the Copyright Office, the term of copyright and the termination of transfer rights remain the same, as if Prince had been credited as the author in the first place. 17 U.S.C. 302(c), § 408(a), (d). This has already been done for many of these pseudonymous works, such as “Manic Monday.” The heirs could choose to leave the registration pseudonymous, but that would likely result in a shorter term of copyright. Prince used pseudonyms primarily in the early part of his career, and works published pseudonymously before 1991 and left unclaimed would expire earlier than the 2086 expiration of works credited to Prince.

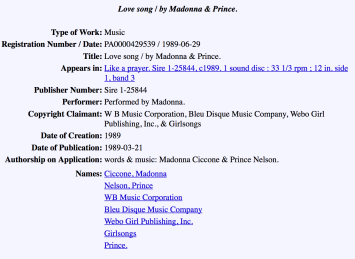

Some of Prince’s Jointly Authored Works will be Protected Even Longer

In the case of a joint work prepared by two or more authors who did not work for hire, the copyright endures for a term consisting of the life of the last surviving author and 70 years after such last surviving author’s death. 17 USC 302(b). Prince occasionally wrote with co-authors who have also passed, so the copyright in those songs will last (under current law) until 2086. Many of Prince’s co-authors are still alive, such as Madonna for “Love Song,” so the copyright expiration cannot yet be determined, but will last beyond 2086.

In the case of a joint work prepared by two or more authors who did not work for hire, the copyright endures for a term consisting of the life of the last surviving author and 70 years after such last surviving author’s death. 17 USC 302(b). Prince occasionally wrote with co-authors who have also passed, so the copyright in those songs will last (under current law) until 2086. Many of Prince’s co-authors are still alive, such as Madonna for “Love Song,” so the copyright expiration cannot yet be determined, but will last beyond 2086.

The Works Made for Hire Battleground

Prince’s heirs may challenge any assertion that any of Prince’s works were “works made for hire.” When a company hires an artist to create a certain kind work and follows certain statutory requirements, the company is considered the author of the work as a work for hire. For a work for hire, term of copyright is 95 years from publication or 120 years from creation, whichever expires first. Songs like Prince’s embody two copyrights: the copyright in the composition, and the copyright in the recording. Record contracts typically provide that the recording is a work for hire created by the record label as author, not the artist. As such, the termination of transfer is unavailable for works made for hire. However, that status has been regularly challenged in courts, and it may turn out that despite the language of a particular record contract, Prince’s recordings were authored by Prince and transferred to the record label, rather than considered authored by the record label as works for hire. Although this determination affects the term of copyright, it is more impactful on the termination of transfer right, and likely to be a source of litigation as the termination rights in Prince’s works mature over the next seventy years.

Joint Authorship will Complicate Everything

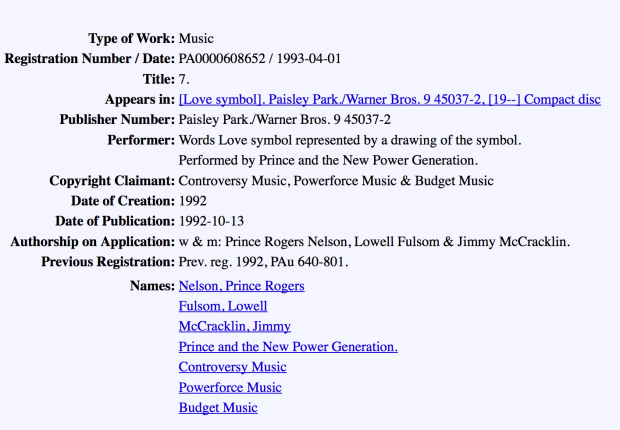

Most Prince songs are credited in the copyright registration solely to Prince, like “Purple Rain” and “1999.” Other songs have multiple authors. The Prince and the New Power Generation song “7” has three authors — Prince and the late blues musicians Lowell Fulsom (d. 1999) and Jimmy McCracklin (d. 2012). Joint authorship affects both the term of copyright and the termination of transfer.

The termination of transfer is granted to any majority block of owners of the right to terminate. If Prince wrote a song with one other living co-author, then termination can only be affected by the co-author plus Prince’s administrator. Where Prince is co-author with more than one person, the transfer could be terminated without Prince’s administrator’s participation. However, even if Prince’s heirs and administrator object to such a termination, they are entitled to an equal share of any further exploitation of such works.

It gets more complicated where Prince’s collaborators are also deceased. Prince co-authored some songs with his jazz musician father, the late John L. Nelson, such as “Computer Blue” from the Purple Rain album. In such a case, the termination of transfer will depend on both Prince’s administrator and his father’s heirs. John L. Nelson has several living children (Prince’s siblings) and grandchildren who could claim an equal part of the right to terminate transfer. Whichever of them (or their descendants) is alive at the time of the maturation of the right to terminate a transfer of one of those co-authored songs will need to cobble together a majority group of Nelson’s children and grandchildren that owns the right to terminate, and also Prince’s administrator. This complexity is multiplied where there are multiple deceased authors, as with the song “7.” It is possible that heirs who were shut out of a will would nonetheless own or share the late author’s right of termination. These rights can be organized by an attorney in the present, even if they can’t be exercised until some future date.

Post Mortem Rights of Publicity

Although not a part of copyright law, the right to exercise certain copyright rights will intersect with Prince’s rights of publicity. Certain states have laws or court decisions that allow people to protect the use of their personas in commerce. As of this writing, Minnesota protects rights of publicity through court rulings (Lake v. Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., 582 N.W.2d 231 (Minn. 1998); Ventura v. Titan Sports, Inc., 65 F.3d 725 (8th Cir. 1995)), but does not have a right of publicity statute, and is silent on whether those rights exist after the celebrity has passed. However, Minnesota’s Senate and House of Representatives recently introduced a new bill that would establish a broad right of publicity that would cover Prince — the Personal Rights in Names Can Endure Act. The PRINCE Act would grant extended publicity control to the artist’s estate and limit commercial use of his name and likeness by others. It would last for the celebrity’s life plus at least 50 years, thereafter for as long as it is still in use, and would apply retroactively to celebrities who died within 50 years before the law’s passage. In Prince’s case, the right would descend to his siblings, and be further sellable or descendible by them, until at least 2066. Any exercise of copyright in Prince’s work would likely be accompanied by a consideration of his post mortem rights of publicity.

Change in Copyright Law will Likely Benefit Prince’s Heirs

Because we’re talking about such a long time, copyright law itself may change. Copyright law has gone through major revisions in the United States that have affected the term of copyright. Each copyright regime has stayed in place for decades since the first Copyright Act of 1790. Major changes came in 1831 (which was essentially preserved in the Confederacy under 1861 and 1863 Confederate acts, and honored after the war) and again in 1909. The current regime is the Copyright Act of 1976, which federalized copyright law, removed formalities, and came into effect on January 1, 1978 — coincidentally the dawn of Prince’s career. Each of these revisions expanded the rights of authors and more forcefully protected intellectual property. This gradual increase in copyright protection is not surprising, as the United States evolved from a country that largely imported the creative works it consumed, into the world’s largest exporter of intellectual property. One recent change in copyright law added the administrator as a possible claimant for termination of transfer — previously, it had only been children or grandchildren. We can expect another change in the law between now and the expiration of copyright in Prince’s works in 2086. We can further expect that such a change will increase protection of his works, either in length of term or some unforeseen manner.

Prince as a Model for Future Application of Copyright Law

Because of the administrator’s ownership of the right to terminate, there must be an administrator in power at least through 2086, when Prince’s works finally enter the public domain. The administrator will have responsibilities beyond 2086, to exercise the termination rights for works Prince co-authored with collaborators who have not yet passed as of 2016. During his lifetime, Prince was a tireless advocate of his rights as an artist, using copyright law to control and protect his artistic footprint, even when it seemed like it would cost him more than it would gain. For different reasons, it appears that more contentious exploration of copyright law will continue to be part of his legacy. Needless to say, it will be a long time before Prince’s estate is fully settled. Any successful artist would be wise to consult with an attorney about the effect of copyright law on their estate, and not leave behind the uncertainty faced by the Prince heirs.

______________________

Further Readings:

17 usc 203; 17 USC 302.

Lawyers Begin Digging Into Prince’s Estate

http://minnesota.cbslocal.com/2016/05/08/lawyers-prince-estate/

Prince’s sister says he had no known will, asks court to appoint an executor to oversee estate

http://www.chicagotribune.com/entertainment/music/ct-prince-estate-no-will-20160426-story.html

Prince’s estate: Potential legal red tape highlights importance of a will

http://www.cbc.ca/news/prince-will-siblings-estate-1.3569831

Prince Ahead Of His Time On Many Things Including His Business Dealings And Copyright Terminations

http://www.musicthinktank.com/mtt-open/prince-ahead-of-his-time-on-many-things-including-his-busine.html

Prince Gains His Catalog in Landmark Deal With Warner Bros.; New Album Coming

http://www.billboard.com/articles/news/6062423/prince-deal-with-warner-bros-new-album-coming.

Prince Brings Publishing In-House

http://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/prince-brings-publishing-house-693754

A link to the PRINCE Act

https://www.revisor.mn.gov/bills/text.php?number=SF3609&session=ls89&session_year=2016&session_number=0&version=latest

Rothman’s Roadmap to the Right of Publicity: Minnesota

http://www.rightofpublicityroadmap.com/law/minnesota

Minnesota state legislature introduces bill inspired by Prince’s death

http://consequenceofsound.net/2016/05/minnesota-state-legislature-introduces-bill-inspired-by-princes-death/

Listen to the Copyright On! Podcast Episode 4 — it’s a Caselaw Chitchat with Jeff Bowen, the Obie-Award winning composer and lyricist of the Tony-nominated musical [title of show] and “Now. Here. This.” Jeff has been writing songs since he was a kid, and now writes songs that appear all over the modern musical theater landscape. He shares his process, and his insights into the seminal music plagiarism case of Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music, also known as the “He’s So Fine / My Sweet Lord” case.

Listen to the Copyright On! Podcast Episode 4 — it’s a Caselaw Chitchat with Jeff Bowen, the Obie-Award winning composer and lyricist of the Tony-nominated musical [title of show] and “Now. Here. This.” Jeff has been writing songs since he was a kid, and now writes songs that appear all over the modern musical theater landscape. He shares his process, and his insights into the seminal music plagiarism case of Bright Tunes Music v. Harrisongs Music, also known as the “He’s So Fine / My Sweet Lord” case.